What is Philanthropy?

What is Philanthropy?

We welcome Rev. William H. Lamar IV, Pastor at Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, DC, as our guest writer this week. This article is based on remarks Rev. Lamar shared at a gathering we hosted last fall focused on nurturing generosity in Black faith communities.

by Rev. William H. Lamar IV

The title of this essay is a question. Our relationship to questions is unhealthy. Paying homage to the great poet Billy Collins, we want to tie questions to chairs with rope and torture confessions from them. We want to beat questions with hoses until the thinnest of so-called answers emerge. We feel questions to be unwise or imprudent unless they quickly yield to predictable answers that neither challenge how we live nor how we order our churches, institutions, and societies. This hesitance to dance with questions shows itself in our journalism, our entertainment, our theology, our economics, and our politics. We do not ask questions to be transformed. We ask questions so that we may continue to walk the paths we now tread, with little deviation in the direction of that light that would assure mutual flourishing. We keep our heads down and put one tired foot in front of the other convinced that we are right, others are wrong, and that it is a waste of time to turn our thinking over once more, like rich soil in which beautiful possibilities might take root and grow.

I want to turn our thinking as one might turn a kaleidoscope, trusting that each rotation will cause brilliant colors and captivating shapes to dance before our mind’s eyes. Here again is the deceptively simple question before us: What is philanthropy?

The first word here belongs to our peerless ancestor, author, filmmaker, and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston. She chased questions about Black cultural production around this nation. And each question took her on another dangerous, thrilling, and difficult journey. Questions were not a means to an end for Miss Hurston, they were open doors in a spacious mansion of human discovery. She found treasure in that mansion; treasure this brutal, beautiful nation could not mar. Miss Hurston’s companions were sometimes God and always a chrome-plated pistol just in case. Turning us in new directions is always dangerous. It always will be.

Move from Sorrow’s Kitchen

“I have been in sorrow’s kitchen and licked out all the pots. Then I have stood on the peaky mountain wrapped in rainbows, with a harp and sword in my hands,” wrote Zora Neale Hurston. Philanthropy is the act of permanently closing sorrow’s kitchen. Philanthropy is forging a path for all human beings and the created order to move from sorrow’s kitchen to the peaky mountain and to be wrapped in rainbows of beauty and abundance.

We must say a word about sorrow’s kitchen. Its existence is not the will of God. We must never think it normal. We must never think it an inevitable feature of God’s good creation. Extractive capitalism tells us that this is just the way it is. But true philanthropists see and know differently. Sorrow’s kitchen is filled with patrons and employees because misanthropes exploit human labor, land, and love. I have traveled the globe and have not found respite nor sanctuary from the fast food of the United States. Likewise, sorrow’s kitchen is marked by a dismal ubiquity. The languages and spices change. The ingredients slopped upon plates and hidden beneath eternally existing plastic boxes are the same. Billions and billions are served misery because we clothe misanthropic systems in mendacious garments of democracy and meritocracy. And these systems grow fatter and fatter when the pots in sorrow’s kitchen are licked by our fellow human beings. Philanthropy, as they say, you have one job. To permanently close and demolish sorrow’s kitchen. To make sure new franchises never pop up again. Yet, the harp yet plays and the sword must be wielded. To that we must return.

Money, Generosity, and Philanthropy

Our views of money, generosity, and philanthropy are derived not from the best of our theological heritage, but from a capitalist system. Money is to be earned at all costs and hoarded. Generosity is quick absolution, an ineffective attempt at washing off the grime of lucre. Philanthropy is the tossing of pennies to drown out the sounds and sights emanating from sorrow’s kitchen.

Money, generosity, and philanthropy are not to be used to keep this tattered world from crumbling. They are to be used in the service of helping new heavens and new earths appear among us now. Those who suffer do not want repair; they want revolution. And those with resources and power are fighting against the reign of God by pretending that what they benefit from is divinely sanctioned. Our views of money, generosity, and philanthropy do not smell like the manger, the cross, or the empty tomb. Our views smell like Wall Street, Madison Avenue, Congress, and executive suites. Our theologies are soaked in acquisition and accumulation. The church is not standing in the way of ideas and systems that crush bones. We are their loudest cheerleaders. If your church is not cheering the systems but silent, please be clear: your silence is cheering by default.

Philanthropy and the Gospel of John

I love etymology. Philanthropy means human lovers. The Black community has always been a philanthropic community. What we have done has never been just for us, but for humanity. In William Edward Burghardt DuBois’ magisterial work Black Reconstruction, he writes about the South Carolina legislature when it was controlled by Black men. They passed laws for universal public education – they wanted to educate not only their own children, but the children of those who once owned their flesh. That is true philanthropy. Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church was built by women who sold food, not for themselves, but to give for the construction of the church. Our sublime stained-glass windows were paid for by people who had been enslaved. We must all follow these examples of radical love for humankind.

What do we find in the second chapter of the Gospel of John? Let us ask a question to broaden ourselves, our interpretation, our ethical possibilities. I believe we find Jesus’ most generous act, his crowning philanthropic moment. Passover was near. There were energetic moneychangers. There was the braiding of a whip of cords, by Jesus no less!

What was Jesus’ most generous act? I appreciate what he did for Jairus’ daughter but I don’t want to stop there. The fishes and loaves blessed thousands, but I don’t want to stop there. Bartimaeus regained his sight. The brother by the pool of Bethsaida danced away in the light of God. But Jesus’ most generous act is extracting, driving away, pushing devourers out of God’s temple. What Jesus seeks to do here is not just address the needs of individuals. He seeks to bring into fruition a system that no longer exploits God’s people. True generosity is to eliminate systems that take away the opportunity for generosity to take root and to grow.

The church often stops when we feed one individual. We must get rid of the system that produces hunger. Churches often stop when one family is educated. We must get rid of the system that produces ignorance. Jesus violently flips over tables. He seems to be saying, “Do you know who presides over this injustice? The religious leaders!” Every unjust system requires the imprimatur of religion. If we do not reframe generosity as creating systems where humans will flourish, the pain our communities face will increase. God’s people are waiting to hear the melodies of the harp of justice and beauty about which Miss Hurston wrote. But God’s people also know that the sword is required, aggression is required, confrontation is required. These systems will not go gentle into that good night. Like Miss Hurston, we must be willing to fight to build the possible. We are aggressive and confrontational, even violent about preserving what is. Jesus braided a whip, ran out exploiters, poured out their coins, and flipped their tables. He picked up his sword. Will we follow Jesus?

What is philanthropy? To remove our people from the licking of pots in sorrow’s kitchen. To lift humanity as we trek up peaky mountains where we all will be wrapped in the rainbows of God’s largesse. This is difficult work, but it is the work to which we are called. We must take axes to tables of oppression and plant and tend forests of flourishing.

William H. Lamar IV is pastor of Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, DC. Ordained as an itinerant elder in 2000 at the Florida Annual Conference of the AME Church, Lamar has also served congregations in Monticello, Florida; Orlando, Florida; Jacksonville, Florida; and Hyattsville, Maryland. A 1996 magna cum laude graduate of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, Lamar earned the Bachelor of Science degree in Public Management with a minor in Philosophy and Religion and a certificate in Human Resource Management. In 1999, he earned the Master of Divinity degree from Duke University. Lamar is currently a doctoral student in the inaugural cohort of Christian Theological Seminary’s Ph.D. program in African-American Preaching and Sacred Rhetoric.

William H. Lamar IV is pastor of Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, DC. Ordained as an itinerant elder in 2000 at the Florida Annual Conference of the AME Church, Lamar has also served congregations in Monticello, Florida; Orlando, Florida; Jacksonville, Florida; and Hyattsville, Maryland. A 1996 magna cum laude graduate of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, Lamar earned the Bachelor of Science degree in Public Management with a minor in Philosophy and Religion and a certificate in Human Resource Management. In 1999, he earned the Master of Divinity degree from Duke University. Lamar is currently a doctoral student in the inaugural cohort of Christian Theological Seminary’s Ph.D. program in African-American Preaching and Sacred Rhetoric.

Question for Reflection

Rev. Lamar’s reflections draw on his tradition’s scriptural images and lift up teachings about generosity, justice, and power—all important considerations in the work of philanthropy. What sacred teachings on generosity, justice, and power come to mind in your community’s tradition?

Expanded Perspective: Philanthropy & the Black Church

Here we offer this spotlight on Metropolitan AME. This short video highlights the congregation’s creative partnership with philanthropy and nonprofits to address environmental injustice, by easing the heat for communities of color and low-income neighborhoods through a “smart surfaces” coalition.

Here we offer this spotlight on Metropolitan AME. This short video highlights the congregation’s creative partnership with philanthropy and nonprofits to address environmental injustice, by easing the heat for communities of color and low-income neighborhoods through a “smart surfaces” coalition.

American Jewish Philanthropy 2022

With antisemitism as well as the Jewish community’s charitable giving both surging in the United States amid the current war between Israel and Hamas, a landmark study recently released has revealed that American Jews who have experienced antisemitism give an average of almost 10 times more to charity than those who have not had those experiences.

The American Jewish Philanthropy 2022: Giving to Religious and Secular Causes in the U.S. and to Israel study, from the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy and the Ruderman Family Foundation, is one of the first major reports on Jewish giving trends in America in the past decade. The report’s publication comes as antisemitic incidents in the U.S. have increased 388% since the start of the war over the same period in the previous year, according to the Anti-Defamation League.

Exploring Jewish Traditions and Relational Philanthropy

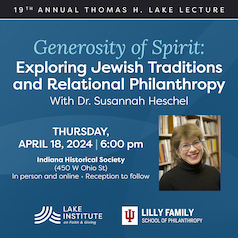

Dr. Susannah Heschel will join us on April 18 for our 19th annual Thomas H. Lake Lecture to speak on “Generosity of Spirit: Exploring Jewish Traditions and Relational Philanthropy.”

Dr. Susannah Heschel will join us on April 18 for our 19th annual Thomas H. Lake Lecture to speak on “Generosity of Spirit: Exploring Jewish Traditions and Relational Philanthropy.”

At its core, philanthropy is about relationships, but in our increasingly polarized and disconnected world, how do we form these relationships and develop a generosity of spirit? Our religious traditions have often demonstrated the essential nature of relationship between one another, within communities, as well as between the human and divine. As a renowned scholar of Jewish studies and a present-day leading voice for modeling dialogue across difference, Dr. Susannah Heschel will discuss the ways in which religion broadly and Jewish tradition specifically can help us better practice philanthropy as the love of humanity.

Subscribe

Insights, a bi-weekly e-newsletter, is a resource for the religious community and fundraisers of faith-based organizations that provides:

- Reflections on important developments in the field of faith and giving

- Recommended books, studies and articles

- Upcoming Lake Institute events