Rural Abundance Overflowing

Rural Abundance Overflowing

by Meredith McNabb

In the United States, the season of Thanksgiving often brings displays and images of ‘cornucopias’—horns of plenty—in which grains, fruits, nuts, and other signs of a successful harvest are overflowing onto the table as a representation of gratitude and celebration for plenty. It’s an ancient symbol of agrarian abundance—but for many urban and suburban contexts today, it has more to do with craft stores and florists’ work than with the actual abundance of harvest and a farmers’ work.

A Natural Counterbalance to Scarcity

At a recent conference exploring rural Christian congregations’ engagement with their communities, scholar and Spring Forest monastic community leader Elaine Heath observed that rural communities of faith are uniquely attuned to the abundance of God—and to the goodness of slow, patient work in participating in that abundance. The scarcity mindset for so many congregations and their surrounding communities has a natural counterbalance in the wisdom and experience of farmers, ranchers, and gardeners. Growth isn’t instantaneous, and there’s real work and risk involved, but there’s genuine abundance when the harvest comes. (A Thanksgiving display of an overflowing crate full of zucchini and tomatoes might be an even more accurate image of abundance for many in 21st century North America.)

Recognizing one’s own assets and organizational impact is a crucial aspect of any religious organization looking to invite others to participate with their time or their money. It’s the difference, in many cases, between transactional, or even desperate requests, and the kind of invitations that can transform both the givers and the recipients. When leaders in any geography have a solid foundation in their congregation or organization’s reason for being and its unique asset base for living that out, those invitations are easier to make and are more effective. Rural and small town settings have a more uphill journey as they grapple with significant challenges and disparities in their communities.

United Methodist Bishop Tom Berlin, leading 700-some churches across Florida, points to disparities in rural infrastructure, mental health services, workforce development, access to capital, high speed internet access, educational institutions, and hospital closures—but notes that these significant needs of people in rural areas might actually be exactly where rural congregations have assets and strengths. “Focus on the needs of people, not the need of the [congregation] for people,” Berlin said.

Recognizing Intangible Abundance

Rural relational capital, resourcefulness, history, and intergenerational connections contribute to a robust if sometimes intangible abundance among the people in rural communities—but it’s an abundance that’s woven deep in rural congregations. But all this also points to an economic abundance rooted in rural congregations that often goes unnoticed in the wider conversations about the economic challenges—perhaps because those intangibles are ‘just what we do’ for many of the rural congregations themselves.

In McCordsville, Indiana, for instance, the annual Lord’s Acre Festival dates back more than 70 years, with people volunteering and participating in the fish fry (and in more recent years, face painting) for their whole lives—and while they’re glad of the fundraising that comes through the event (Pastor Daniel Payton notes that the event raises tens of thousands of dollars annually), they’re even more focused on the annual connection and the fun of pulling together to make it happen.

In McCordsville, Indiana, for instance, the annual Lord’s Acre Festival dates back more than 70 years, with people volunteering and participating in the fish fry (and in more recent years, face painting) for their whole lives—and while they’re glad of the fundraising that comes through the event (Pastor Daniel Payton notes that the event raises tens of thousands of dollars annually), they’re even more focused on the annual connection and the fun of pulling together to make it happen.

Partners for Sacred Places has long studied the “economic halo effect” of churches, synagogues, and other houses of worship on their neighborhoods—and their first study of specifically rural congregations¹ calculated an average annual economic impact of between nearly half and three-quarters of a million dollars each as they serve as community hubs, oasis points of needed childcare, and centers for support for individuals and families as well as simply existing as economic actors in their communities. It’s an impact far outpacing their budgets—and it tells a whole different story about what it can mean to invest in a rural congregation for an individual giver or a philanthropic institution. These congregations can be robust settings for all manner of good, far beyond their own walls and members.

The census trends point to the real potential oversupply of congregations in rural areas, as the National Congregations Study notes that “nearly half of [US] congregations are in rural areas (25 percent) or small towns (22 percent), while the 2020 census found that only 6 percent of Americans live in rural areas and 8 percent in small towns.”But those numbers suggest that partnership, consolidation, and experimentation are called for, not disinvestment or despair.

The abundance of rural congregations (and other religious organizations) may be overlooked by folks outside those communities—or even by those inside them who have become accustomed to a scarcity lens. But there is more than meets the eye, in both resources and opportunities, in rural religious communities.

¹Partners for Sacred Places studied rural United Methodist Christian congregations in North Carolina and found that on average, each congregation generates $735,800 in annual economic impact. Excluding the congregations located in the top 10% and bottom 10% of the sample size, they found an average annual economic impact of $488,598 each.

Questions for Reflection

-

- When you’ve been part of the same community for a long time, it’s not always easy to see what’s right in front of you. What are some examples of abundance in your congregation that may be taken for granted?

- Urban, suburban, rural — our surroundings impact the way we view our work. How does the setting in which your organization is situated inform your vision and mission?

Expanded Perspective: The Community Capitals Framework and the Rural Church

by Bo Prosser

If you look up a working definition for the word rural, you find will this: not urban. That is not very helpful! Rural is much more than farmland, volunteer firehouses, and Aunt Bessie’s Biscuit Barn. There is a depth of soul and richness of tradition; there is a grit and a determination that many say is the “backbone” of our nation.

And the rural congregation is the heartbeat. Amazing Grace is sung almost every Sunday, and most members take stewardship seriously. As one gentleman told me recently, “During Covid we all upped our giving to the church. We weren’t gonna let our church fail. We even took up some extra for our pastor and her family.”

Researching the elements at work in the rural community, Flora and Flora (2013) developed the Community Capitals Framework. Seven capitals are identified, and the framework can be used as a tool for making a strategic plan for now and the days to come.

As a part of the Campbell University Rural Clergy Initiative, Foreman and Nelson (2021) expanded this framework to specifically focus on the rural church.

One of the identified capitals is financial capital. This analyzes the financial resources available for a church to do work now and in the future, including current financial resources and any opportunities to accumulate wealth for future development. Many rural churches are discovering the importance of healthy financial policies. They also are starting or adding to endowment funds from special gifts and bequests. And these churches are finding ways to partner with other community groups to enhance their communities.

One church in rural North Carolina has constructed a Solar Farm on an isolated piece of land given to them. A church in rural Virginia has paid for running water to be available for the Community Garden. And several rural churches are setting up scholarship funds for their youth to help defray the cost of college.

There is so much creativity in the rural parish. Post-pandemic, rural pastoral leaders are reframing their call and the importance of preaching generosity and abundance. Pastoral leaders are learning how to ask for help and for money, and church members are responding positively. As one parishioner told me, “Preacher, the only people who don’t like to hear preaching on money are the ones who ain’t giving. We are okay being challenged.”

There’s a grit about the rural community and the rural church. The people just won’t let their church fail. The heartbeat for our faith is strong in the rural church.

Bo Prosser is a catalytic coach and adjunct instructor with Lake Institute on Faith & Giving. For more on the Community Capitals Framework, contact him at bo.prosser@gmail.com.

Creatively Letting Go

St. Paul’s United Methodist Church used their extra church building to support a nonprofit focused on one of the most urgent and challenging social problems in their community. This is one of many stories on our Faithful Generosity Story Shelf that shares vignettes of congregations and other religious organizations who are using their buildings and other assets in new and generous ways.

St. Paul’s United Methodist Church used their extra church building to support a nonprofit focused on one of the most urgent and challenging social problems in their community. This is one of many stories on our Faithful Generosity Story Shelf that shares vignettes of congregations and other religious organizations who are using their buildings and other assets in new and generous ways.

Distinguished Visitor on December 6

How do religious diversity and generosity help make a vibrant society?

How do religious diversity and generosity help make a vibrant society?

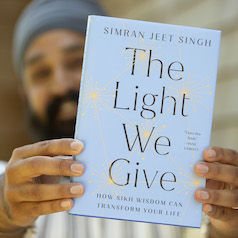

Join us for A Conversation with Simran Jeet Singh, author of the bestselling book, The Light We Give: How Sikh Wisdom Can Transform Your Life, to explore how generosity toward one another and the power of religious diversity can promote a healthy civic society.

Indiana Historical Society

Wednesday, December 6 at 6:00 pm ET

Subscribe

Insights, a bi-weekly e-newsletter, is a resource for the religious community and fundraisers of faith-based organizations that provides:

- Reflections on important developments in the field of faith and giving

- Recommended books, studies and articles

- Upcoming Lake Institute events