FAITHFUL GENEROSITY STORY SHELF

Story Shelf Map

Find stories from the Faithful Generosity Story Shelf by location

Browse stories:

The trust built by a church in Galveston, Texas, is translating into better access to treatment at a free clinic staffed by health care providers and housed in former Sunday school classrooms.

The trust built by a church in Galveston, Texas, is translating into better access to treatment at a free clinic staffed by health care providers and housed in former Sunday school classrooms.

Adapted from A church and health center collaborate to provide care for people with substance use disorder by Lindsay Peyton for Faith & Leadership.

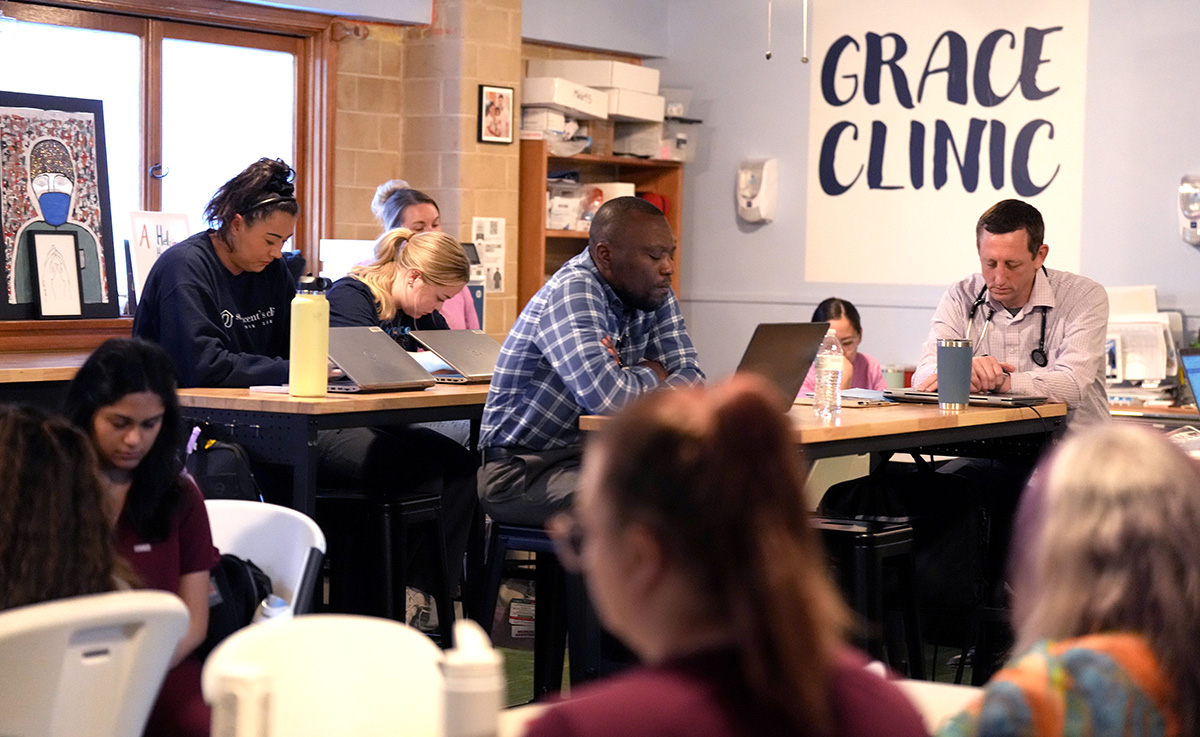

A United Methodist church in Galveston, Texas, has transformed unused Sunday school classrooms into a free, walk-in clinic providing treatment for people with substance use disorder (SUD).

Galveston Central Church has long served the city’s unhoused and underserved residents, offering meals, showers, bicycle repair and other essential services. That history of service created deep trust within the community — a foundation that made it possible to expand into health care.

Today, in partnership with the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) and St. Vincent’s Hope Clinics, the church hosts both a primary care clinic and a dedicated SUD Clinic offering medication-assisted treatment at no cost.

Each Tuesday morning, an interprofessional team of doctors, medical students, counselors, social workers, peer coaches and researchers gather on the church’s second floor to see patients. Walk-ins are welcome, appointments are not required, and patients do not need insurance. About 20 patients are typically seen during the three-hour clinic session. The environment is intentionally nonclinical: no white coats, no badges, and a strong emphasis on dignity and respect. The Rev. Michael Gienger, the church’s co-pastor, describes the clinic’s approach as “flipping treatment on its head.”

Many patients have been coming to the church for years and view it as a safe place. That familiarity lowers the threshold for seeking care, especially for people who have faced stigma or rejection in traditional medical settings.

Patients receive medications such as Suboxone, which reduces cravings and overdose risk, along with mental health care and social services. Shelby (who, like other clients, requested that only her first name be used in this article), struggled with fentanyl addiction. She credits the clinic’s free medication and nonjudgmental care with helping her achieve seven months of sobriety. Lacey, who lost her insurance, relies on the clinic to stay clean. Angela, sober for more than a year, says the clinic saved her life after a physician recognized signs of kidney failure and rushed her to the hospital.

The church’s evolution into a hub for health care began during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Galveston Central partnered with UTMB to host a vaccine clinic for Spanish-speaking and unhoused residents. While mistrust in the health care system and logistical barriers often keep vulnerable populations from accessing care, the church learned that the trust it had earned made it a safe place to ask questions, see familiar faces, and receive health services.

In 2021, the church launched Grace Clinic, a pilot program offering free primary care in their unused Sunday school space. The program expanded in 2022 and later added the SUD Clinic in response to rising overdose deaths. Because of the success of Grace Clinic, Rev. Gienger was confident in the ability to provide nonjudgmental care, which would become even more critical in treating addiction. Funding from an external partner helped make the expansion possible.

UTMB faculty say the clinic also provides invaluable training for students, who learn to treat addiction and poverty with empathy while working as part of an interdisciplinary team.

Since opening, the clinics have helped patients regain housing, recover mobility, return to work and rebuild their lives.

“We’ve seen folks that have had their lives dramatically changed,” Gienger said. He spoke of a patient who lost his sight, then his job and finally his housing. Now, after obtaining corrective surgery through the clinic, he has a job as a hotel manager.

While relapse is recognized as part of recovery, leaders emphasize that success often begins simply with showing up — and feeling welcome enough to return.

The clinics have reshaped church leaders’ understanding of ministry. Gienger and co-pastor the Rev. Julia Riley view mental and physical health as inseparable from spiritual well-being. They also see church property as an asset meant to serve the community every day of the week.

“Sunday is the least interesting thing we do here. It’s nothing compared to what people are experiencing with the resurrection on Tuesday and Thursday,” Gienger said.

Though small in size, Galveston Central’s impact is far-reaching. By opening its doors to unconventional partnerships and redefining how care is delivered, the church has created a model of compassionate, accessible treatment — one that offers not only medical care, but belonging and a chance at renewal.

Instead of asking people to come to their church for a hot meal, Emmanuel Episcopal operated a free hot dog cart around the city to feed those experiencing homelessness.

Instead of asking people to come to their church for a hot meal, Emmanuel Episcopal operated a free hot dog cart around the city to feed those experiencing homelessness.

By Ray Marcano

In Bristol, Virginia, hot dogs are more than one of America’s favorite foods.

The Emmanuel Episcopal Church, under the leadership of The Rev. Dr. David L. Bridges, purchased a hot dog cart last year to feed the unhoused population.

He asked a parishioner, who happened to be homeless, how he and the church could help the community. “Well,” the parishioner said, “everybody needs to eat, and living on the street, it’s tough to eat.”

Dr. Bridges became the church pastor in May 2024 and began looking at ways to connect with the community. Another parishioner recommended a program he called “Feed My Sheep,” which would bring food to those in need. Dr. Bridges looked into buying a food truck, but spending $50,000 on a vehicle and paying for ongoing costs was too big of an expense.

Then, true to the saying that “God works in mysterious ways,” one day Dr. Bridges saw a car pulling a hot dog cart and thought—that’s how we get food to the people. He raised $4,500 and purchased a cart from a social media site.

The hot dog cart idea was a paradigm shift. Instead of asking people to go to a church for food, the church would bring food to the people.

“We started out going down by the public library on Wednesdays in the winter, because a lot of the unhoused people hang out there. And so we’d feed them there and then go over to city park for the same thing, just to feed whoever’s out there.”

But it’s gotten harder for the church to do its work. The city made it illegal for the homeless to stay in certain areas, so the hot dog cart has only gone out once this year. The new rules have forced the unhoused into a wooded section away from downtown. Dr. Bridges said he’s thinking through how to get them food without giving away their location.

Feeding those in need matches with the church’s mission.

“In our baptismal covenant, we agree to uphold the dignity of every human being and to meet the needs of the needy among us as best we can,” Dr. Bridges said.” Our covenant makes us responsible for our neighbors, those around us, and this is one way of showing people that this is who we are. We’re followers of Christ who said, ‘Feed my sheep,’ and that’s why we’re here. No agenda, no cost, no obligation.”

As with any new venture, there’s risk. “Perhaps the risk is that no one would show up. But I knew that wasn’t going to be the case. Maybe people feel that there’s a little bit of risk in trying to join people together, especially across racial barriers.”

His partnership with AME Pastor The Rev. Dr. William Ward, a Black man, has gone a long way toward showing the community that people of different backgrounds can love and care for each other. “We spend as much time together in public as we can, because people need to see us in public,” Dr. Bridges said.

Now, Dr. Bridges has his sights set on other community projects.

Dr. Bridges and Dr. Ward held a community block party with food and prayer, but more importantly, “We displayed unity, that we were all one family, not here with an agenda,” but to “be in community.” He asked himself, “What can we do?” The answer: “We can do this more often,” and he’s working on a plan to do so.

They want to reopen a now-closed AME Church as a community gathering spot that can help meet the needs of a community with a declining population, rising poverty, and a tough job market.

“I think that since the building is debt-free, we can join together and do this, and I think we can get grant monies to do it,” Dr. Bridges said.

I bet they’ll have hot dogs.

A church turns their parking lot into a free-of-cost auto repair shop twice a year to ensure those with limited resources have safe and well-functioning vehicles.

A church turns their parking lot into a free-of-cost auto repair shop twice a year to ensure those with limited resources have safe and well-functioning vehicles.

By Dan Holly

Mention Shonte Johnson’s old van to the car-care team at Triangle Church of Christ in Durham, N.C., and heads start shaking.

“That van was on the road longer than it should have been,” said Rick Fuller, referring to Johnson’s 2002 Toyota Sienna.

Rick Overturf, the church’s lead evangelist, said the van gave them nightmares. “Have you ever heard the saying, ‘Makes a preacher want to cuss?’ ” he quipped.

They’re both joking around; in fact, helping people like Ms. Johnson is why the team exists.

The team does not charge for repairs. It even provides lunch for the people waiting for their vehicles.

Johnson, a 46-year-old certified nursing assistant, smiles as the car-care team gently teases her about her old van on a recent Sunday afternoon in November. She has since moved on to a Toyota Camry. Now she brings that in for regular maintenance.

“This has meant everything to me,” Johnson said while watching the team circle around and crawl under her Camry, inspecting and testing.

“I wouldn’t even be on the road with what I can afford – none of this stuff,” Johnson said. “I’ve been a single mom since I moved here. …They’ve been a Godsend.”

Twice a year, Triangle Church holds car-care days for single moms. The events – named the Single Moms Car Project – are held in the church’s parking lot. At the Nov. 1, 2025 event, the team had 16 cars signed up and about 20 volunteers from the church doing the servicing.

Overturf explained that these car-care days are the most visible part of the car ministry; throughout the year, they also do follow-up or as-needed repairs – whether at the church, at a church member’s home or wherever they’re needed.

Though the team is staffed by volunteers, the operation is more professional than amateur. Overturf and his son, Logan, who works at the church and serves as the team’s official leader, are ASE-certified mechanics. The church has a huge arsenal of equipment including two tall tool chests, several hand-held diagnostic computers and a larger computer that can both read and manipulate diagnostic data.

The church budgets $1,200 a month for the Single Moms Car Project, which it has offered since 1999.

Asked about the motivation behind it, Overturf does not have a complicated answer. “It’s just something I knew how to do growing up,” he said. “And so it was a way to serve in the church, particularly our single moms who come from a very difficult background. … We saw plenty of them driving around with kids in the car, and they were just unsafe. You’re like, ‘We’ve got to fix that.’ ”

Some church members have donated to the car-care ministry –beyond the monthly budget. Others volunteer regularly and have become well versed in vehicle repair.

Jeff Kiel has done both.

“I think the main reason is just thinking about what we can do to be a blessing to both members of the church and obviously members of the community as well,” said Kiel, a senior manager at Nvidia. “God has given us so much. I can’t help but think I’ve got to find ways to be able to help.”

The program has been invaluable to the single moms in the church. “I was a single mom with three children, and I worked two and three jobs,” said Denise Kendall. “If I had not had my car, it would have been very hard for me to provide shelter for my children.”

The women often struggle with challenges beyond solo parenting.

“Right now, I’m unemployed, so this is helping me with affordability. This is saving me about three to four hundred dollars…I’ve actually been on disability for two years,” said Jayne Brayboy Back, who has two children, ages 15 and 13.

As much as the car-care team helps the single moms, it helps the volunteers as well. Lincoln Billado, 17, attended the Nov. 1 event – watching and learning. “I learned about electrical systems and wiring and why newer cars use coils instead of wires. And, honestly, this helped me a little bit serving-wise, sort of developing a good mentality around that.”

A comedian-turned-pastor opened an alcohol-free comedy club in his church's basement to support the sober community.

A comedian-turned-pastor opened an alcohol-free comedy club in his church's basement to support the sober community.

By Ray Marcano

Renaissance Vineyard Church builds community through the gospel, outreach and—comedy?

Yes. Comedy.

The church holds a monthly “Joke Gym,” a PG-13 rated show in the basement of its facility in Ferndale, MI, a suburb of Detroit.

Co-lead Pastor Drew Fralick used his background as inspiration for his church-comedy club idea, which he called “pretty controversial, really out-of-the-box.” But he’s a big believer in what he calls “in-between spaces” that connect church with community.

Fralick knows something about the funny business. He spent 11 years in China performing as a comedian and opening comedy clubs.

Upon moving back to the U.S., Fralick and his wife, Laurie, joined the church of about 100 congregants. In 2021, the church’s founding pastor announced he was leaving and asked Fralick if he’d like to succeed him.

“I thought, I’ve never been a pastor. I don’t really know anything about that. And he goes, ‘Well, you’re a therapist and a comedian. That’s a pretty good start for any pastor post-pandemic.’”

Now, Fralick and his wife serve as co-pastors.

Fralick combined his Master’s in mental health counseling and passion for comedy into a community experience.

Each Friday night, the church holds Celebrate Recovery, a Christian 12-step program for drugs, alcohol, and trauma.

Fralick decided that laughter could help attendees take their mind off their troubles, if only for a little bit. After the Celebrate Recovery meeting at 6:30 p.m., Fralick opened an alcohol-free bar at 8 p.m., followed by the comedy show at 9 p.m.

The bar became a community draw for people who wanted to have a fun night out without consuming alcohol.

“It exploded,” Fralick said. “The sober community is pretty big in Metro Detroit. We’ve had a lot of those people come through our doors, people who maybe haven’t stepped foot inside of a church in maybe 20-30 years or they wouldn’t be caught dead in a church, they’re coming to this in-between space.”

While his church board supported the idea, he ran into some opposition from parishioners and comedians.

The comedians wondered how they could perform in a church environment and follow the Joke Gym’s clean comedy mandate. “I think that a really good artist can fit within constraints,” Fralick said.

But he quickly learned he had to set boundaries for what was and wasn’t appropriate material.

“In the beginning, we said, ‘Let people use their best judgment,’ which was not a good idea,” he said, laughing. “I learned 85% of (comedians) are very smart. They’ll read the room, and they’ll say, ‘Oh I’m in a church, maybe I shouldn’t do this.’ And 15% of people just don’t care. We’ve hemmed it in a bit, because comedians will just go right to the edge if you let them.”

Off-limit topics include glorifying drug use and violence, and pedophilia and rape.

Some members of the congregation worried about the joke topics and that comedians would poke fun at religion. (Fralick has poked fun himself, like with his routine on a privileged Adam and Eve.)

Fralick pushed on, painting the church basement walls and ceiling black so it had a more comedy club vibe. The basement already had a stage, and he created an area for the bar. With a little paint and elbow grease, he created the club space with little money.

Over time, the opposition waned. Comedians now contact Fralick hoping for a chance to perform. Most of the shows are donation-only with just a few ticketed events for bigger names. Every week, the space, with about 40 seats, sells out.

Church goers mingle with community members, an important part of Fralick’s in-between philosophy.

“We need a place where the religious world and the outside world can interact,” he said.

Now, some two and a half years later, the Joke Gym has become a community staple, and Fralick is proud of the church’s uniqueness.

“This church values authenticity,” he said. “It’s not a stuffy religious environment. So having a comedy space helps us not take ourselves too seriously, to poke fun at stuff, and have a good time. This church does a lot in the community, so being able to host events aligns with that.”

When a church invites a line dancing group to use its basement for practice, a mutually beneficial relationship develops.

When a church invites a line dancing group to use its basement for practice, a mutually beneficial relationship develops.

By Kelly Dunlap

One fall evening in a small North Carolina town, a group began to congregate, uninvited, in the pavilion of New Salem UMC. A well-intentioned member of the church set off to inform the group that they couldn’t gather on their property, but when Pastor Steve Bergkamp caught wind of what was happening, he ran after them to insist that they were welcome to stay.

The unexpected visitors were a recreational line dancing group that had lost access to their usual facility and needed a place to dance. Bergkamp invited them to return as they wanted and offered the use of the church’s fellowship fall, free of cost.

The members of New Salem UMC were not surprised by, or resistant to, these new regulars on their property. Since beginning at the church just two years prior, Bergkamp had built up trust among the congregation and conveyed his desire to cultivate new relationships in the community.

Bergkamp had told the congregation: “The church isn’t going to grow by what we do on Sunday mornings. Our goal is to utilize our property and buildings Monday – Saturday, then Sunday will take care of itself.”

However, while church growth is welcomed, these community interactions are not covert strategies to grow the flock. Bergkamp has made sure that it’s clear, both in his congregation and the community, that there are no strings attached when community groups use their space—there are no requirements for visitors to join the congregation or claim religious beliefs. If there were expectations, Bergkamp believes that “people will sniff that out and know we’re not authentic.”

The congregation went through a discernment process during the recent schism in the United Methodist Church, in which some churches chose to disaffiliate. New Salem decided to stay in the UMC and through those discussions on values and vision, the congregation identified that they cared more about having an impact on the community than growing attendance on Sunday mornings. This clarity of vision gave Bergkamp a “green light” to put energy toward relationships outside of the church. A very small number of members, already unhappy with New Salem’s decision to stay in the UMC, left the church over the its approach to community outreach.

Those who stayed had a renewed energy to make space, literally, for new life in the church. Church members have been cleaning out the church library and old Sunday school rooms so that they can be used by the community. Bergkamp says that attention is being paid to respecting and preserving their heritage, while not letting it be a hindrance to what they believe God is calling them to today.

Church trustees even decided to spend $12,000 to replace the fellowship hall floor to better host the line dancers. The dancers became very active in the church’s fundraisers for this project and even other ministry efforts.

While there was no expectation the dancers would support the church in this way, Bergkamp did say he’s given one stipulation for their use of the space: that people of all backgrounds from the community were welcome to participate for free. The group eagerly agreed.

Building community partnerships is not a new territory for Bergkamp. Prior to becoming a pastor, he served for 35 years as a Park Ranger and Superintendent, including being a “burn boss” responsible for prescribed fires. In these roles he organized community groups to assist in park operations. He recognizes that some of those outreach and organizing skills are being put to use in his new role as pastor.

But Bergkamp doesn’t see New Salem’s outreach efforts as exceptional, but rather as a part of a larger trend of congregations asking how they can use their properties in service to the community.

And New Salem’s new ways have stirred curiosity in the town about the church. “We’ve become known as the church that has a full parking during the week,” Bergkamp says.

A chance encounter with a man experiencing homelessness led to a comprehensive church-based ministry to help the most vulnerable in the community.

A chance encounter with a man experiencing homelessness led to a comprehensive church-based ministry to help the most vulnerable in the community.

By Ray Marcano

A chance encounter with a homeless man led to a church-based outreach program that helps vulnerable members of society.

The homeless outreach effort, by New Covenant Church in Thomasville, GA, also shows that community connections can be more valuable than cash.

The outreach began by chance. About two years ago, senior pastor Dave Allen and his wife, Alli Allen, joined another man who was going on a “street feed” to take food to the homeless.

The Allens encountered a man living in the woods who had spent time in prison and just been released from a crisis center. They gave him a meal and companionship and talked to him about how he wanted to give himself to the Lord.

The next morning, the man showed up at New Covenant. He had walked to town from the woods, with no shoes and blistered feet. His determination gave the Allens the strength to take a leap of faith. With no money and few connections, the couple decide to start the homeless outreach ministry.

“Our statement is ‘Love, mend, train, send,’ so we love them where they’re at, help with the mending process and do training” to help them improve their lives, Alli Allen, who co-pastors with her husband, said.

Thomasville, with a population of almost 19,000, has its struggles. More than one in five residents live in poverty and it has one of the highest crime rates in the country for a city its size.

Speaking of the area where some of the homeless lived, Alli Allen said, “We didn’t know it was a really bad area. It was a wooded area, a lot of sex trafficking, drugs, violence, murder in the area.” But the Allens pushed forward, convinced of the need for their ministry.

The church board support the effort, as does the small congregation of about 75. But the Allens were still responsible for driving the project, raising money and attracting volunteers to build their vision.

They have rallied the community for in-kind contributions. Local restaurants donate food and Dave Allen drives a van borrowed from another church to shuttle the homeless to and from programs at New Covenant.

But the in-kind donations aren’t enough to sustain the program. So the Allens get small cash donations from family members and friends — $50 here, $200 there — to buy grits, coffee and other items. Local churches also pitch in with a few dollars here and there.

“It’s all about building relationships,” Alli Allen said.

From that one feed two years ago, the program has now grown to include activities and meals two to three days a week. Thursday’s a big day. The attendees can take showers in the church locker room, eat breakfast and lunch, and drop off laundry. Alli and a few volunteers do the cooking and serve upwards of 25 meals on any given day.

The outreach also includes a Bible-based program that helps the homeless understand the challenges they face, which includes addiction. The Allens both have a mental health counseling background, and they use scripture to share the message that, “with God’s help, they can have the power to overcome and get to the root issues of why they’re doing drugs or alcohol or having a non-productive lifestyle,” as Alli put it.

There are risks, and big ones. Some of the homeless have mental health issues, still struggle with drugs, and can be violent.

“I’ve had our front doors ripped off and stuff stolen,” Alli Allen said. “I have a friend in Chicago that did homeless ministry, and he got stabbed. He made it, but barely. Because we get close, there’s always a risk. But I think when you see lives radically changed and true love happen, you take the risk.”

The risk has certainly paid off and made a difference in lives, like the homeless man that Allens first encountered. He moved into a tent on church property, and the Allens helped him get a job. He now helps with the street feed and Dave Allen continues to mentor him. More importantly, he’s reconnected with his mother, an alcoholic who now volunteers two days each week at the church.

The Allens take Matthew 22:37-39 to heart: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart…. Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself”

As Alli Allen said, “We just love people.”

A Detroit church has created a community haven where visitors can not only find spiritual support and connection, but can clean their clothes, too.

A Detroit church has created a community haven where visitors can not only find spiritual support and connection, but can clean their clothes, too.

By Ray Marcano

A Detroit church has created a community haven where visitors can not only find spiritual support and connection, but can clean their clothes, too.

Back in 2018, Mack Avenue Community Church opened The Commons, a laundromat and coffee shop. It gave the neighborhood “a space to congregate, to meet, to connect, to cross paths, to hang out, to engage with each other,” church pastor Leon Stevenson, said.

On its face, combining a laundromat and coffee shop under one roof might seem an odd pairing, like putting pickles on a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. The project came together after the church met with community members to learn how it could help the struggling area. The church learned that people needed a place to wash their clothes.

“Our vision is to see communities transformed, both physically and spiritually, starting right here with our own,” Stevenson said. “So, on the spiritual side, the church is excited to invest in people and lead with discipleship and see people grow in Christ.”

Investing in Detroit’s zip code 48214 meets the church’s vision of helping neighborhoods flourish. Nearly 30 percent of local residents live below the poverty line.

Moreover, The Commons is located 1.3 miles east of the church in an area that needs support. The laundromat/coffee shop sits across the street from a vacant lot and a mini-mart. Some houses are boarded up, others in drastic need of repair. Crime is also a problem, as the zip code is one of the more dangerous in the country, according to Crimegrade.org.

Eight years prior to opening The Commons, the church started a nonprofit for community development and other initiatives like an after-school program, legal clinic and sports program.

But The Commons was a massive undertaking. Through philanthropy and grants, the nonprofit raised $1.4 million to purchase a vacant building, renovate it, and buy laundromat equipment.

Stevenson’s board and small congregation of 90 people back the project. But the wider church community that had partnered with Mark Avenue on other projects was more reserved, and that hurt.

“They were like, good idea, but let’s see how that goes. Get back to us when you get halfway through it,” Stevenson said. He had the financial resources to complete the project, but wanted more spiritual support to carry him through times of doubt.

“I think that we all want to be affirmed,” he said. “We want to know that this risk we’re taking is worth it. Knowing that people are behind you and believe in you and are praying for you, really can make the difference.”

The area provides a challenge and risk for The Commons. Some have tried to steal the tip jar. Others have come in angry, broken things in the store and accosted staff. Stevenson is amazed that when these things happen, customers take action, as if to say, “No. Not here.”

“Our customers have jumped behind the coffee bar to make sure our people were safe,” Stevenson said. “You don’t do that unless it’s a place you care about. You don’t give of yourself unless you felt other people love and care for you. That’s what gets me emotional sometimes, thinking that people would fight for this place in that way.”

The Commons is priced with the community in mind. A cup of coffee costs $1.89, and a breakfast sandwich is $3. A small load of laundry costs $3.50 to wash and $0.25 to dry. You can even buy laundry detergent ($0.50 for a half cup, $1 for a full cup).

It’s a big undertaking that has paid off for a neighborhood that needs it. Everything — the building’s location, its services, and its perseverance in the face of poverty — fits into the Mack Avenue Community Church’s philosophy.

Stevenson said, ‘What we hope you say about our church is that because they exist, my quality of life is better.”

In an effort to make amends, the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland established a $1 million reparations fund to benefit Black communities.

In an effort to make amends, the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland established a $1 million reparations fund to benefit Black communities.

By Dan Holly

Sitting just south of the Mason-Dixon line – the line separating slave states from free states in the early history of this country – Maryland was located just barely in slavery territory. But the state was deeply into slavery nevertheless. The commodities produced by slaves “provided the foundation for Maryland’s economy,” according to a state history document.

Today, strikingly, Maryland is a leader in reconciliation efforts between Black and White residents, including reparations initiatives for Black residents. Among the more prominent of these projects is one undertaken by the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland, which, in 2020, established a $1 million seed fund to be disbursed to programs in Black communities.

The initiative for the fund came from Bishop Eugene Taylor Sutton, who, in 2008, became the first bishop of color in the diocese. When the diocese’s convention passed a resolution establishing the fund, Bishop Sutton commented: “Passing the resolution is in recognition of our collective complicity and contributing to the impoverishment of Black communities. I had nothing to do with enslaving persons. I’m not guilty of that, but I have a responsibility. … I know we don’t all agree that this is the best vehicle to make amends. We all do agree, I’m quite sure, that we will do all we can to eradicate the sin of racism off the face of the earth and repair the damage that it has done to this nation, this state and our communities for centuries.”

Since 2022, the diocese has awarded over $655,000 in reparations grants to more than a dozen organizations, and the grants will continue. (The fund was set up so that grants can come from interest, not principle, and can continue in perpetuity.)

Standards for use of the Reparations Fund have never been set in stone. From the beginning, there was controversy. Diocese archives show that there was a lively debate in 2020 when the resolution establishing the plan was proposed: “Those who spoke against the resolution did so not as much in opposition to the concept of reparations, but with questions as to how the money will be wisely and faithfully spent,” the archives state.

A committee was established to disburse the funds. Suggested uses included:

- Improving housing assistance programs that help Black Americans purchase homes.

- Developing mixed-use housing that supports socio-economic diversity.

- Bringing desperately needed services such as grocery stores, urgent care centers, and community centers to communities, and

- Developing meaningful job-training programs in partnership with corporations and local businesses for actual job placement.

The chosen winners have depended a lot on the strength of the application, according to J. Jason Hoffman, Director of Communications for the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland. In the third round in 2024, $50,000 grants went to African American Resources Cultural and Historical Society, Baltimore Children’s Peace Center, BRIDGE Maryland, Doleman Black Heritage Museum, and Marian House.

For the fourth round, in 2025, the grantmaking focus has changed some to emphasize start-ups. “Fifty thousand dollars is really not a lot of money,” Hoffman said, “but it can have a great impact on a start-up.”

The $50,000 grant that the Doleman Black Heritage Museum got in 2024 played a “vital” role in helping the group accomplish its mission, said Alesia Parson McBean, the museum’s project director. The museum, located in Hagerstown, Maryland, is dedicated to preserving African American culture and history. The grant allowed the museum to restore stained glass windows from a local church that had been torn down. The windows were more than merely decorative; in slavery times, the church was a stop on the Underground Railroad and the windows show images that secretly alerted escaping parties that the church was a safe house, McBean said.

The restored windows will be displayed at the museum’s new home, which is under development.

“We [African Americans] are 14% of the [county] population, and the median income is less than $40,000, so people who have an interest in preserving Black heritage, history and culture don’t always have the disposable income to throw at it,” McBean explained. “This grant came at a wonderful time.”

Two people in a good position to assess the impact of the diocese’s Reparation Fund are the Rev. Nancy H. Hennessey, rector of Sherwood Episcopal Church in Cockeysville, Md., and Stephen Gibson, a retired school principal from Baltimore. They were co-chairs of the first Reparations Fund Committee.

Both can point to success stories for individual grant recipients, but they cannot offer hard data on the fund’s overall impact, because the grants are not set up in a way that specific metrics of success can be applied.

“From the very beginning our approach was to say, if we are truly looking at reparations, we are not going to micromanage and look at what you did, dollar for dollar,” Gibson said. “That was never the intent of the Diocese of Maryland. The intent was to go through the discernment of letting God lead us to organizations that are trying to do the right things. We have people in the committee who are assigned to that particular organization to take a look at it and work with them. But we do not ask for a lengthy report where we say, ‘Show me how you spent each and every dollar.’ ”

More important, Rev. Hennessey said, is the impact on people. “It’s about building relationships – particularly for the White community, to understand what barriers are still in place now. …A lot of our churches were built on the backs of slaves. So that’s a whole ’nother component of it. Eventually, I hope, each of our congregations will do a deep dive into their own history. Some have done a fabulous job already. Others are still trying to come to terms.”

“We’re a little unorthodox, but you know, that’s the point,” Rev. Hennessey reflected. “And it is all about restitution.”

When a church member deeded a large plot of land to his church, the congregation leased 80 acres for solar farms, leading to a surplus of income and the Gratitude Project.

When a church member deeded a large plot of land to his church, the congregation leased 80 acres for solar farms, leading to a surplus of income and the Gratitude Project.

By Dan Holly

The First Baptist Church of Mount Olive is a small, old church in a small, struggling town in eastern North Carolina. But due to a stroke of luck about 20 years ago – or perhaps it was divine providence – the church has something even a megachurch in a prosperous suburb would love to have: a steady source of income above and beyond congregation donations. Good income.

A few years ago, church members decided they needed to do something with their extra money: give it away.

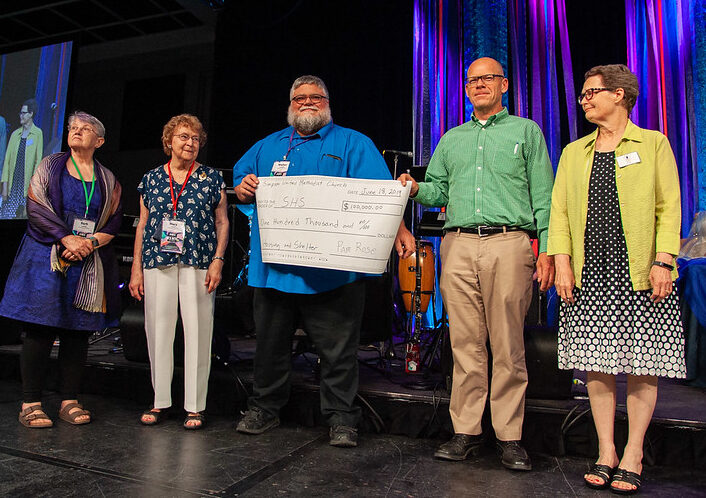

Rev. Dennis Atwood, the former pastor of 22 years, did a series of sermons on gratitude that culminated with a call to take $100,000 and put it into a fund to “make a difference.”

His sermons evidently were effective. He put the proposal to a vote and it was a unanimous “yes.”

They decided to call it the Gratitude Project.

“I didn’t begin the sermons with that [the Gratitude Project] in mind…but I thought we had to do something concrete about poverty, education, the lack of affordable housing in our town. We are one of the poorest areas in the state. …I thought $100,000 would be a good starting point.”

The seeds of the Gratitude Project were planted back in 2003. That was when a church member deeded more than 200 acres to the church in his estate. In 2013, Birdseye Renewable Energy was looking for tracts of land for solar farms. The company contacted the church and the end result was leasing two parcels – a 38-acre tract and a 39-acre tract – for solar farms. The farms bring in $80,000 per year to First Baptist Church of Mount Olive.

Bryan King, a church member who is an attorney, was appointed chairman of the four-member committee designated with deciding how to give away the funds.

The committee first researched other places that had done something similar. “We tried to approach it from the get-go that this wasn’t going to be just charity, just giving money away,” King said. “It was more about trying to address structural problems in our town, the biggest one being poverty.”

Mount Olive has a population of just over 4,000, according to the town’s website. The median household income is just below $42,000 and the poverty rate is 27 percent, according to Data USA.

Mount Olive is almost a Southern cliché. Railroad tracks divide the town and one side is mostly Black, with many rundown and overcrowded houses; the other side is largely White and middle class. First Baptist sits on the White side of the tracks – one block in. The 350-member church is overwhelmingly White.

The Gratitude Project gave out 10 grants for projects ranging from housing repair to piano lessons.

Some of the grants had a direct impact on poverty. For instance, an $18,000 grant to the Wilmington Area Remodeling Ministry (WARM) went for extensive repairs to the home of a man who had fallen behind on upkeep due to health issues.

Other grants took an indirect approach, such as the $12,000 given for football equipment for the Mount Olive Hurricanes, a youth football club that mainly serves young people from low-income families, according to the club’s director Ronnie Wise. The club’s equipment was so old that the club’s future was in peril, Wise said. The grant ensured its future, he said.

The last of the $100,000 was disbursed in January 2025.

Rev. Atwood would like to see a second phase of giving, as more money becomes available, focusing on affordable housing. He also has written a book about his journey to gratitude. He hopes other churches will follow his church’s example.

“The Gratitude Project was just a way to throw another stone into the pond and create ripples,” he said. “You could affect people in other ways; this is one way to do it. I think it gave us a little bit of fresh air and a boost in our approach to missions in the community. It’s a model – a model other churches could use when they reach out to their community.”

To learn more about The Gratitude Project, contact Rev. Dennis Atwood at dennisratwood@gmail.com.

A church and mosque collaborate to power—and empower—their neighborhood by installing solar panels on the church roof.

A church and mosque collaborate to power—and empower—their neighborhood by installing solar panels on the church roof.

By Dan Holly

The main mission of Shiloh Temple International Ministries is to advance Biblical principles, like any Christian church. But when the Minneapolis, MN, church was approached with the idea of installing solar panels on their roof to serve the surrounding community, the idea fell on fertile soil.

Head Pastor Richard D. Powell Jr. saw merit in the idea, particularly because it could be helpful to the community, a neighborhood in north Minneapolis with many low-income residents.

“It’s important that the faith community be supportive of solar-powered energy because the mission of the church is to be a lighthouse for the community,” Rev. Howell said.

It was really a matter of square footage that the church was chosen for the project. “We chose Shiloh Temple because they had a huge roof,” explained Julia Nerbonne, executive director of Minnesota Interfaith Power & Light, a group that, according to its website, “works in partnership with multifaith communities and all Minnesotans to co-create a just and sustainable world.” Shiloh also happened to be in a community where Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light had other ongoing projects.

The group partnered with Cooperative Energy Futures, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit whose mission is “to empower communities across Minnesota to build energy democracy through solutions that are clean, local, and ours.” Together, the two groups helped Shiloh develop a solar array on the church’s rooftop — 630 panels that provide 204 kilowatts of power. It opened in 2017.

The array of panels provides power to neighborhood residents who subscribe to it; currently, 25-30 homes are subscribers. The cost is lower than residents pay for traditional sources of energy.

That was good news for neighborhood residents such as Noy Koumalasy.

“To me and my family it means an awesome opportunity,” Koumalasy said. “Once we subscribed to the Shiloh array it was definitely less bills for me.”

The project also provided jobs for some residents; one requirement of the project was that the installation team be at least 50 percent people of color.

Keith Dent, resident of the north Minneapolis neighborhood where the church is located, worked on installing the solar panels.

“Working on this solar garden especially feels wonderful being that I’m a resident of north Minneapolis and I’m a subscriber to the actual solar array,” Dent said.

Edward Owens of the St. Paul NAACP sees the project as a boon for the community.

“Solar energy is an opportunity for us to move forward,” Owens said. “Solar energy is an opportunity for the community to work together.”

The project had benefits beyond saving money and helping the environment, according to Nerbonne. “One of the cool things about this project is that Masjid An Nur, a mosque, and Shiloh Temple, a large African-American church, are working together to make this happen,” she said.

The solar array provides energy to both Shiloh Temple and Masjid An Nur in addition to community residents.

Imam Mohammed Dukuly said the mosque is “proud to be part of this process.” He added: “We believe that this process will restore economic justice to this community.”

Interfaith cooperation and understanding is another benefit of the project, Rev. Howell said: “Isn’t it amazing that we can get along? We may have different viewpoints and ideologies, but isn’t amazing how we can work together and make a difference in the community?”

NOTE: Comments from Pastor Richard Howell, Imam Mohammed Dukuly, Noy Koumalasy, Edward Owens and Keith Dent were taken from a YouTube video produced by Minnesota Interfaith Power & Light.

A church's fixer-upper parsonage becomes a community center to preserve Latino culture and bridge cultural, generational, and denominational gaps.

A church's fixer-upper parsonage becomes a community center to preserve Latino culture and bridge cultural, generational, and denominational gaps.

By Dan Holly

When Cassy Nuñez became lead pastor of Salem United Methodist Church in July of 2021, she inherited a church in a low-income part of Baltimore. The lack of financial resources in the neighborhood forced the church to think a little differently about funding its ministry than it might have otherwise.

“We needed to do a lot more fundraising and be more creative with what we did have,” Nuñez recalled. “I started getting to know community organizations. The church started to become more of a community center. Other things happen here Monday through Friday that are of benefit to the community.”

The church’s higher profile in the community became a matter of opportunity meeting preparation. One of the activities the church hosted was a Covid Vaccine Clinic. One of the attendees was Angelo Solera, founder and executive director of Nuestras Raices, Inc. (“Our Roots”), a local group with the mission of educating, preserving and promoting Baltimore’s Hispanic/Latino culture.

Solera mentioned to Nuñez that the group was looking for a space. They had been meeting in coffee shops, restaurants, and libraries and were looking for a permanent home. The day of the Covid Vaccine Clinic, Solera had an appointment to look at a building that he thought might fit the bill.

It just so happened that Salem United Methodist Church had an old parsonage next to the church, a home for the pastor – if it were livable. But it wasn’t; its problems included walls that leaked when it rained, a nonfunctional basement, and lights and windows in disrepair.

“It was not in a state that we could live in it,” Nuñez recalled. “We could use it for other things….but it would have been very expensive to fix up.”

The church did not have the money and the building stood empty. Nuñez mentioned the parsonage to Solera and told him that it might be another option if the building he was on his way to look at didn’t work out.

As it turns out, it didn’t. Instead, Nuestras Raices took over the old parsonage rent-free for three years. They were able to fix it up with a $45,000 loan from the France-Merrick Foundation, a philanthropical organization “devoted to supporting the people and organizations that make the Baltimore region vibrant and diverse.”

Nuestras Raices transformed the parsonage into Casa de la Cultura (“House of Culture”), which opened in August of 2022. Casa de la Cultura is central to Nuestra Raices’ mission, Solera said. Among the activities the group has held there are art exhibits, theater and dance productions, arts and craft workshops, and guitar classes – all representing Hispanic/Latino culture in some way.

“Casa de la Cultura is the first and only educational and cultural empowering center in the state of Maryland,” he said. “The Latino community is comprised of people from 25 different nations. When they come to the United States, they’re very detached from their home country. When they try to adjust to American culture, they often lose their own culture.”

Casa de la Cultura, he said, “is a place where people can be who they are and become renewed to who they are. …This is a place that helps preserve the richness and diversity of the Latino culture.”

A recent exhibit at La Casa de la Cultura featured Dominican folklore. The artist, who goes by Lusmerlin, said the exhibit shared a part of the culture she grew up with in Santo Domingo. “It was magical to see people from all backgrounds, not only Hispanic, to be enthralled and interested in our stories,” Lusmerlin said.

Pastor Nuñez sees La Casa Cultura as related to the church’s spiritual mission but not in some specific, planned way. “Salem has become a gathering place for the community, and not just people who come to church on Sunday morning,” she said. “The church is also full Monday through Saturday. …This church is everybody’s church.”

One thing she is proud of is how the church has contributed to bridging gaps among various denominations – a goal that is important, she said, because the Latino culture is dominated by Catholicism. Dialogue with other denominations is needed.

“Our mission is to be a spark for the community,” Nuñez said. “No matter what denomination, you are welcome.”

Scottsville Church of Christ stepped forward, without hesitation, to run a food distribution program when an urgent need arose in their community.

Scottsville Church of Christ stepped forward, without hesitation, to run a food distribution program when an urgent need arose in their community.

By Ray Marcano

Food insecure residents in Allen County, KY., faced a problem.

The church that had been running a food distribution program for years could no longer do so, threatening to leave thousands of people without access to the free meals they needed.

Enter the Scottsville Church of Christ in Scottsville, KY., which stepped forward, without hesitation, to fill a void and use its ministry to help community members in need.

“When the opportunity presented itself, everyone was on board and excited to take on this new challenge and role in the community,” Terry Stinson, the church secretary who helps administer the food programs, said.

The small church is having a big impact locally. It now administers three food programs that serve hundreds of households each month.

Scottsville volunteered to take on the food distribution responsibility “because of the need in the community. This was a beneficial program for the community, and we wanted just to step in and carry it on,” Stinson said.

The need is certainly there. Allen County sits in a rural area of the state and abuts the Tennessee border. Nashville is the nearest major city and it’s 52 miles away. In Allen County, 14% of residents face food insecurity, according to Feeding America. Furthermore, 16.5% of the county’s 20,588 residents live in poverty, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. More than three dozen areas in Allen County are considered a food desert, according to one report.

Given these concerning numbers, there’s a clear need for reliable and consistent food distribution. With its new duties, Scottsville now runs three food distribution programs. It participates in the two Feeding America programs it took over in September — one for seniors 60 and over and one emergency food assistance program for anyone in the county who meets income requirements. Those programs provide food once a month.

It also participates in a retail program through Feeding America in which the church picks up surplus food from a local retailer and distributes it weekly. Neighbors come to the church, get a bag, and can fill it with milk, produce, frozen items, or whatever’s available. Stinson estimated that though this retailer program, the church distributes hundreds of pounds of food each month.

The church relies on a dozen or so volunteers to make the program go. In addition to the volunteer hours and Stinson’s time, Scottsville pays Feeding America about $200 a month to deliver the food to the church, purchases boxes used for food, and more.

The community is appreciative. “It’s wonderful. They tell us it’s such a blessing to them that it’s helping them feed their families,” Stinson said.

It’s a major undertaking for a small church of about 150 congregants each Sunday, but one that meets its ministry.

“Well, we’re just trying to help our fellow man.” Stinson said. “You know, we’re told to give food if anyone’s hungry, and we’re just trying to fulfill that commandment and help out in the community to feed the hungry.”

On its website, the church wrote: “We are a group of forgiven sinners striving to serve God and serve others as we journey through life here on earth.”

Nourishing the body and the soul certainly serves others, even when the service can seem like an immense undertaking.

“It seems overwhelming when you start thinking about it,” Stinson said. “But when you come together as a church, you can make it happen.”

Reeman Christian Reformed Church in Fremont, MI., opened Wellspring Adult Day Care in 2016 to help those who need a place to go during the day while giving their caregivers a much-needed break.

Reeman Christian Reformed Church in Fremont, MI., opened Wellspring Adult Day Care in 2016 to help those who need a place to go during the day while giving their caregivers a much-needed break.

By Ray Marcano

A small church in a small town has utilized its resources to make a big impact on the lives of their neighbors.

The Reeman Christian Reformed Church in Fremont, MI., opened Wellspring Adult Day Care in 2016 to help those who need a place to go during the day while giving their caregivers a much-needed break. It took prayer, research, and overcoming initial rejection for the project to move from idea to reality.

Tammy Cowley, Wellspring’s business manager, said, “We hear so many times that (caregivers) could not keep loved ones home as long as we do if it wasn’t for Wellspring.”

In 2015, a congregation member told Nate Kooistra, now the church’s associate pastor and chair of the Wellspring team, there was a need in the larger community for adult daycare services. In addition to giving the adults a place to go during the day, adult daycare would alleviate a little pressure on caregivers, who could have a little break and time for themselves.

Church members prayed about the idea, visited a few adult day care centers, and decided to recommend this new ministry to the church council.

The council, at first, said no.

“We didn’t have enough details for them,” like financial data and a staffing structure, Kooistra said. The council loved the idea, but told Kooistra, “You’re not there yet.”

The initial rejection turned out to be a blessing because it forced the team to dig deeper to get more information. It also reminded the team that people who are unsure at first aren’t necessarily against a proposal. “They just need some time to let it sink in,” Kooistra said

The team visited three adult daycare centers and found one in Indianapolis that served as inspiration because it was a ministry of a church, which is what Wellspring sought to be. The experience helped the Reeman team understand a church-based adult daycare’s activities structure, staffing models and policies. Reeman also learned how to sustain this new ministry through funding sources such as grants, guest fees, Medicare dollars and fundraisers.

Kooistra and his team had another potential hurdle —- he had to meet with and convince the roughly 300-member congregation that an adult daycare fit the church mission.

“Some were excited, several very skeptical, just didn’t quite know why a church would get into this world of things,” he said. “A couple thought it just wouldn’t work. That was a concern for all of us.”

But the congregation approved an effort that fits nicely into the church’s overall mission.

“That’s kind of the mission of our church, to be a neighborhood church, to find ways to use the gifts God’s given us to bless the people he’s surrounded us with. So, it fits … into that kind of merging of those two passions of loving God and loving our neighbor.”

Next, the team talked to local doctors and nurses, who overwhelmingly supported the Wellspring concept. “Every one of them said, ‘I have so many people that could use that,’” Kooistra said.

And then, in the midst of prayer and hope, came an unexpected development that pushed the project over the finish line. Someone from the church donated $10,000 to the ministry, and a local organization provided a grant. Additionally, Wellspring developed other funding sources, such as an auction, and church volunteers help support the mission.

“Those things collectively felt like affirmations that this was where the Lord was leading us and providing a way do this ministry,” Kooistra said.

Now, Wellspring has become an important part of the community at large. Open Monday, Wednesday and Thursday, the program provides lunch, activities, music and more for a maximum of 15 people.

Some attendees use wheelchairs, others have dementia or other ailments. All are welcome.

Wellspring “falls nicely into that sense of loving our neighbors and seeing churches as more than just a place to come for an hour for a week,” Kooistra said. He said a measure of success revolved around these questions: “If your church left the neighborhood, would anybody care? Who would protest? Who would be upset? I think people would be upset now if they lost Wellspring.”

A seminary in Ohio has combined its theological teachings with environmental concerns to feed the body while nourishing the soul.

A seminary in Ohio has combined its theological teachings with environmental concerns to feed the body while nourishing the soul.

By Ray Marcano

A seminary in Ohio has combined its theological teachings with environmental concerns to feed the body while nourishing the soul.

The Methodist Theological School of Ohio created Seminary Hill Farm in 2013 and, at the same time, adopted the term Ecotheology to describe how its unique farming program dovetails with scripture.

“It’s not always been seen, in the environmental justice world, that church can be helpful,” Jay Rundell, the school’s president, said.

The school’s teachings have a historically strong social and ecological justice bent, yet students saw a disconnect between pedagogy and practice. They would eat processed foods in the cafeteria and see staff mowing lawns, examples of “all the things they were learning were hard on the world,” Rundell said. Students “called us out on our hypocrisy,” he added.

MTSO met a prospective student who ended up not enrolling. But the student ran a farm-to-table operation that intrigued Rundell. He was so excited he decided to take the idea of starting a farm to his board.

That’s where the bumps in the road started.

During a board meeting, a long-time member asked a simple question: Why does a seminary need a farm?

“It dawned on me that in all my excitement about doing this, I had missed really connecting [the idea] to the educational program,” Rundell said. “I learned right there I needed to tie it together to be credible.”

By the next board meeting some four months later, board members had begun to shift. They noted that family members, friends, and neighbors were all proponents of sustainable farming. Rundell got the go-ahead to start the farm and, with it, a new course of study MTSO has dubbed Ecotheology.

But then, Seminary Hill ran into more conflict. Through grants and partnerships, the farm had the resources to be successful –tractors, trucks, paid staff and interns, and, most importantly, free MTSO land. With no overhead, Seminary Hill could sell goods cheaper at area markets– the same markets local farmers depended on for income.

“What I thought was giving back to the world felt like an unfair marketplace to people who were in this work,” Rundell said. “That’s a lesson I had to learn in a hurry, to work with the larger ecosystem of people doing this work.”

As a result, Seminary Hill put more emphasis on education and less on profit. The farm has 10 acres but rarely cultivates more than five. (Rundell doesn’t envision it getting any bigger).

Seminary Hill receives occasional funding from The Ohio State University, which Rundell believes is the “only example of a land grant university funding a denominational seminary.”

Other partnerships include AmeriCorps, which provides interns, and the Culinary Institute of America, which uses Seminary Hill as a placement site for aspiring chefs.

The farm builds revenue by selling some of its produce to restaurants and by writing grants. Since the farm isn’t a profit center, Seminary Hill uses excess funds to help the seminary’s community outreach goals. For example, the farm helps stock a food bank and participates in a food and wellness program for underserved and food-insecure communities.

According to its website, the farm grows seven different kinds of peppers, six different types of winter squash, three different types of tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, potatoes, herbs, and more. Seminary Hill has a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) that buys a share of what the farm produces.

Seminary Hill has grown so much and become such a part of MTSO that people search for the term “Seminary Hill” more than they search for “MTSO,” which is the common acronym for the seminary.

“We realized there was more interest in what some felt (was) an appendage or a side business, when all of a sudden that became why people were looking for us,” Rundell said. “And I think that’s when we started to realize this isn’t going to go away. This is a part of who we are.”

A Presbyterian church transforms their unused manse (minister's house) into a home for Afghan refugees, and serve as community for the home's first tenants.

A Presbyterian church transforms their unused manse (minister's house) into a home for Afghan refugees, and serve as community for the home's first tenants.

Abbreviated excerpt from The House Next Door by the Presbyterian Foundation.

What should a church do with property it no longer needs? It’s a question that many congregations are facing. Gateway Presbyterian Church in Colorado Springs, CO owns a house that was used as a manse (minister’s house) for several decades. Gateway members began to consider how they could honor God with good stewardship of this resource they affectionately called “the house next door.”

“It’s a paid-for asset and it had been rental property for 20 years. And the general consensus was, we’re not called to be landlords, but we’re probably called to use that in some kind of ministry,” said Rev. Victoria Isaacs, pastor of Gateway.

A dedicated crew of church volunteers fixed up the house without being entirely sure how it might be used. That is, until Elder Paula Warrell had an idea.

Warrell recalled, “One morning … I read an article saying some of the Afghans would be coming to the United States. I thought: well, here we have this big house and it’ll be ready.”

At that time, hundreds of refugees had settled in the Rocky Mountain region, fleeing violence, persecution, and poverty. Lutheran Family Services is the agency that helps the families settle in the area. The first step is finding them a transitional place to live. That can be a challenge.

“As anywhere in the country, rents are increasing at very high rates,” explained Matthew Cramm of Lutheran Family Services. “We always have to keep in mind that when our families get here, they end up in minimum wage jobs, so we also have to factor in that they’re going to have to be able to pay this rent with the jobs they get.”

More than that, refugees need a sense of community, and that’s one of the unique ways a church like Gateway can help.

“They need care … they need people that understand that starting their lives all over again is extremely difficult,” said Floyd Preston of Lutheran Family Services. “But what makes it easy is churches like this … come alongside the families and help them and alleviate some of that pressure to know that “you’re not by yourself, we’re here to walk with you.”

Just a few months after reaching out to the agency, Victoria got the call that a family from Afghanistan needed a home in Colorado Springs. The house next door was ready.

Victoria visited with neighbors to ensure they would be welcoming. And they were.

The neighbors have embraced this family knowing that circumstances in their homeland were dire.

The family fled the wrath of the Taliban. The oldest son of the family had served as an interpreter for the U.S military in Afghanistan. He emigrated to America six years ago. When the U.S forces pulled out of Afghanistan, his family became targets of the Taliban, who threatened members of the family at gunpoint, twice. The U.S. State Department got the family safely out of Afghanistan, and Lutheran Family Services helped them resettle in Colorado Springs.

The family is learning English and how to find jobs. As they re-build their lives, they feel at home in the house next door.

The refugees reported, “We’re so happy for living in this house. Especially, we are safe here. It’s like a good thing for us that we’re next to the church. They bring some foods for children for us or sometimes some books for us. They have helped us a lot in everything. We are thanking God that we have them here.”

Church members feel a renewed sense of purpose and how God is using the house next door. They spend time with the family and invite them to church events. Through it all, they are following Christ’s command to love their neighbor.

Warrell exclaimed, “It was just meant to be. It was a miracle. We had the place. We had the people working and we all had open hearts to welcome a family. And then we got the best family in the world.”

“Their history has been ‘the little church that could.’ And, yet again, God has allowed them to be able to do something meaningful and life-changing,” said Rev. Isaacs.

A closed church reopens as a worship space for Spanish-speaking immigrants, offering healing sound therapy.

A closed church reopens as a worship space for Spanish-speaking immigrants, offering healing sound therapy.

By Dan Holly

Se pueden leer la traducción en español aquí (Read this story in Spanish)

Congregacion Luterana San Timoteo doesn’t look like your typical Lutheran church, but it especially doesn’t sound like your typical Lutheran church.

For one thing, all members of the church are immigrants from Central and South America, and services are conducted in Spanish. But what makes this Chicago church really different is its use of healing sounds in its services. Singing bowls, rain sticks and other instruments provide sounds that are reminiscent of some of the rituals common in countries from which immigrants came.

The church uses sound therapy not only to make immigrants feel welcome but also as a form of emotional and spiritual healing – something especially needed by church members, many of whom have suffered tremendously in their treks to the United States, church leaders say.

Most of the congregation came to the United States by way of Texas, where they landed after crossing the border from Mexico. Texas authorities, in response to border crossings, have instituted the controversial practice of putting immigrants on buses and sending them to states in the North, leaving them in strange cities with little resources.

“They dropped them off in the streets and in different areas of the city where there were Latino people,” said Rev. Del Risco-Nolla, who co-pastors the church. “They arrived with whatever they had on their bodies – that’s it.”

Congregacion Luterana San Timoteo was planted in 2023 by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, taking over a building on North Kildare in Chicago after another congregation moved out. (Technically, it is still officially a “mission,” not yet a church.)

The church that had been there was populated by the mostly white residents of the neighborhood. As the neighborhood’s demographics changed, the church closed, and the building remained unused until Congregacion Luterana San Timoteo took it over, adopting the Spanish version of the old church name (St. Timothy’s). Only one resident from the old church remained a member.

The new church grew as other immigrants heard about it – it now has about a dozen members but more than 30 attendees at a typical Sunday service.

“There are some people from the neighborhood and some from other areas,” said Rev. Del Risco-Nolla, whose official title is mission developer. “Some travel long distances because they have identified this church as a place where they belong.”

Church leaders used part of a $12,000 grant from the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America to boost their sound healing ministry. The funds came from a grant program aimed at helping the Lutheran Church reach out to nontraditional populations.

Congregacion Luterana San Timoteo was able to buy four singing bowls, two rain sticks, one ocean drum and a Jewish harp.

For many, these techniques are reminiscent of traditions in their homelands such as spiritual healing by shamans and icaros, a form of healing through songs. “It’s part of their identity,” she said.

A classical pianist and a music teacher, Rev. Del Risco-Nolla is certified in sound healing. She uses her training to blend Christian worship with sound healing techniques.

“We worship Jesus Christ,” she said. “It’s just that we use singing bowls in worship.”

With singing bowls, mallets are used to rub bowls in a way that produces a humming sound. That sound is considered calming by many people. Some health-care professionals say the sounds and vibrations can even promote emotional and spiritual healing.

On Sunday, singing bowls are occasionally used as people take communion. Other sound therapy techniques are a prime feature of Tuesday night services.

Healing sounds are one of the things Edward and Jennifer Rodriguez, who have been members of Congregacion Luterana for five months, like about the church. “The music calms me down,” Edward said. “I think it’s relaxing and effective.”

Said Jennifer: “They [members of Congregacion Luterana] were the second people we met and the only ones we have right now.”

NOTE: Edward and Jennifer spoke in Spanish. Their comments were translated using Google Translate.

A NYC church continues its long-term relationship with the theater community and generates needed income by opening rehearsal space.

A NYC church continues its long-term relationship with the theater community and generates needed income by opening rehearsal space.

By Dan Holly

The Church of the Transfiguration in New York City has a lot of things going for it – a prime location in midtown Manhattan just blocks from the iconic Empire State Building; a rich history (it was a stop on the Underground Railroad); and a Gothic-style brick building with national landmark status. But until recently the church also had something of an albatross – it owned property next door that sat empty.

The Episcopal church does not need the neighboring property, which consists of the first four floors of a modern building, for church functions. But it has depended on the space for rental income, according to Katherine Hutt, the clerk of the church’s vestry.

“We had a tenant for many years that provided income needed to support the historic [church] property, which is expensive to maintain,” Hutt said. “They moved out during the height of the pandemic and we were not able to find a new renter.”

The church came up with an oh-so-New York solution – it is now renting the property to theater groups. Hutt explained: “We decided to turn the space into a rehearsal facility for theatre groups and manage it ourselves.”

In early 2022, the empty space was transformed into the Houghton Hall Arts Community. Hutt, who is also president of a communications company, co-founded the community organization.

“More than 50 different groups have rented space: theatre companies, acting schools and teachers, dance groups, clowning and stage combat instructors, play reading groups, and more,” Hutt explained. “…We have also hosted a number of events, including training for public school theatre teachers, a piano festival, a teen theatre festival, black box style performances, and a songwriting collaborative.”

She added: “The long-term goal for Houghton Hall is to replace the revenue that a single tenant provided to the church. While we are still several years away from achieving that goal, we are moving in that direction.”

Hutt says the reaction from groups that rent the space has been “overwhelmingly positive.”

One of the satisfied customers is Urban Angels Acting Workshop. The group uses Houghton Hall for such activities as relaxation, sensory work, improvisation and monologues. “Urban Angels Acting Workshop found a home when Houghton Hall was just starting out,” founder Karen Giordano said. “It’s a welcoming and community-minded, creative space for artists.”

The ties to the theater community are not only practical, considering the church’s location in New York City, but also consistent with the church’s theological tradition and mission. The rehearsal space is named for the church’s first rector, Dr. George Houghton, who was among the first clergy in New York City willing to do funerals for actors.

The church’s website recounts the history that cemented its ties to the theater community:

A few days before Christmas in 1870, Joseph Jefferson, an actor renowned for his portrayal of Rip Van Winkle, approached the rector of the now-defunct Church of the Atonement to request a funeral for his friend and fellow actor, George Holland. Upon learning that the deceased was an actor, the rector refused to hold a funeral for the man in his church. Joseph Jefferson persisted, and asked if there was a church in the area that would hold services for his friend. The rector said, “I believe there is a little church around the corner where it might be done.”

That “little church” was Church of the Transfiguration. (“Little Church” remains its nickname, to this day.)

“The church has had a long history with the theatre community, so this new use for our rental space is a great fit,” Hutt said.

While the arrangement is mutually beneficial for the community and the church, it is more than a matter of convenience; the space is, after all, owned by a church.

“The secondary goal is to strengthen the ties that the church has long had with the theatre community, and we are seeing results from that, as well, including a marriage and a baptism from among our users,” Hutt said. “Although Houghton Hall is not a church outreach program per se, we do think that those in the theatre community who may be seeking a spiritual home would find Transfiguration to be a very welcoming, inclusive, supportive place.”

Churches in Wilmington, Delaware share their commercial kitchens so food entrepreneurs can grow their businesses.

Churches in Wilmington, Delaware share their commercial kitchens so food entrepreneurs can grow their businesses.

Edited excerpt from Cooking up new businesses by using church space creatively by Holly Quinn for Faith & Leadership.

The Wilmington Alliance had a plan. In 2019, the economic revitalization nonprofit in Wilmington, Delaware would launch a commercial kitchen incubator, helping food entrepreneurs build businesses while utilizing vacant spaces in the city.

But converting vacant warehouse spaces into commercial kitchens was more complicated than anticipated. What the project really needed were existing commercial kitchens that were rarely if ever used. Kitchens that could be renovated, rather than built from nothing.

Enter Grace United Methodist Church. Established in 1866, the active church with a magnificent chapel and stained-glass windows is known for its community outreach. At one time, the large kitchen in the basement was used often. By 2019, it was not.

The idea of using a church kitchen seemed impracticable at first. How would a church share space with entrepreneurs from the community? What were the risks? Was it sustainable?

The Rev. Chelsea Spyres was working part time for Grace UMC and Riverfront Ministries in January 2020 when she heard about the project.

“At the time, the Riverfront board was starting to ask, ‘How do we invest more deeply physically in the city?’” she said.

“For Riverfront, the communion table is this reminder of God’s presence with us, of belonging. But also, we talk a lot about how the communion table calls us to create other spaces of belonging and importance. And so when Grace started thinking about this shared commercial kitchen, Riverfront said, ‘this might be the right thing for us to invest in.’”

Today, Spyres is the pastor and executive director of Riverfront Ministries, the operating partner of the Wilmington Kitchen Collective leading the work alongside Wilmington Alliance and the church partners. The Collective currently serves 16 entrepreneurs in two renovated church kitchens — the original space in the basement of Grace UMC and a second kitchen at First & Central Presbyterian Church.

Getting a business in the food industry off the ground is challenging. Food trucks in Delaware, for example, are required to have access to a commercial kitchen, an often insurmountable hurdle for entrepreneurs with limited resources. Those facing the biggest barriers tend to be people of color and women, and the Kitchen Collective’s cohort of entrepreneurs reflects that.

Fulfilling a need

Joanne Graves and her husband wanted to expand their honey business, GravesYard Apiary, by adding herbs to create electuaries, sweet medicinal pastes that are mixed with hot water or milk.

“You cannot do that legally unless you’re in a commercial kitchen,” Graves said.